Explore the resources below to assist in completing this action.

Biodiversity Guidance action 1.2.2

1.2.2 Apply these concepts to your business context

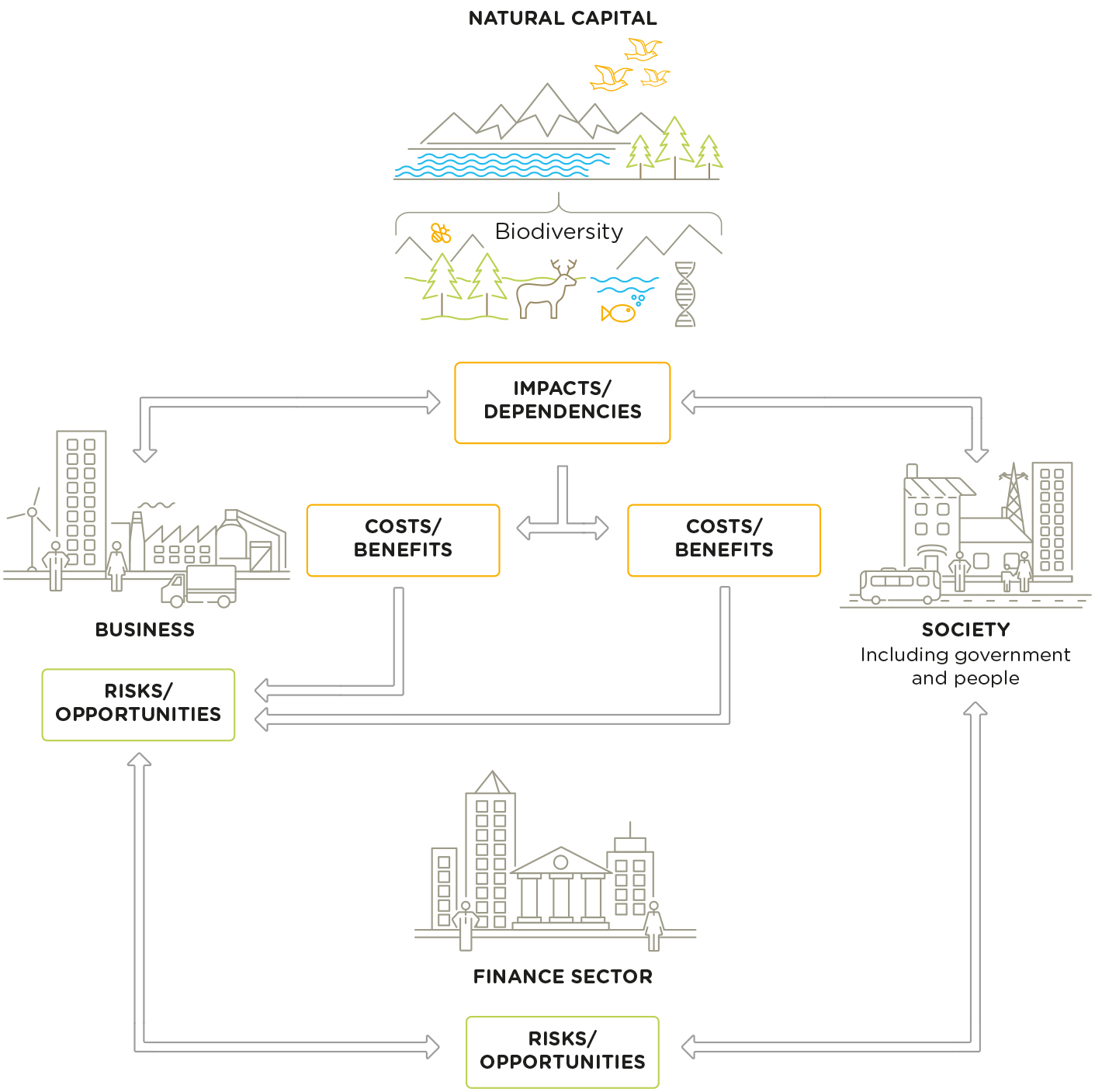

Every business and financial institution depends, to some degree, on biodiversity. Business activities often have negative impacts on biodiversity (e.g., through inputs to production processes, or outputs resulting from business activities). These impacts and dependencies result in economic costs and benefits for business and society (e.g., related to air, water, and soil pollutants, or habitat destruction or preservation). While these generate risks to your business, good management can also create opportunities, either directly or indirectly through the costs/benefits experienced by society (figure 1.2).

As figure 1.2 shows, the risks and opportunities experienced by business and society are transferred to the financial sector through banking, insurance products, and investments such as corporate bonds, stocks, and financial derivatives.

a. Business impacts and dependencies on biodiversity

Impacts

Your business activities may have numerous impacts on biodiversity and natural capital, which can have positive or negative effects. As with other aspects of natural capital, your business impacts on biodiversity occur through impact drivers, which include:

- Business use of natural resources as inputs to production processes, such as water use, terrestrial ecosystem use, or marine ecosystem use;

- Non-product outputs resulting from business activities as well as the use and disposal of products that the business creates, such as air pollutants, solid waste, or disturbances.

Your business impacts on biodiversity may be direct, indirect, and/or cumulative. Indirect impacts are triggered in response to the presence of your business projects or operations, rather than being directly caused by them. Cumulative impacts arise from the combined impacts of your operations, those of other organizations (including other businesses, governments, and local communities), and other background pressures and trends (BBOP 2012a). Similarly, impacts can accumulate over time, so that relatively small impacts of each subsequent activity can add up to a large overall impact. Your business impacts on biodiversity, particularly your indirect and cumulative impacts, may often be non-linear and difficult to predict (this is covered in more detail in the Measuring and Valuing Guidance).

A single business production process may have impacts on biodiversity through multiple direct, indirect, and/or cumulative mechanisms. For example, production of natural fibers in the textiles industry requires use of water and large areas of land for growing crops, and may produce air, water, and soil pollutants, as well as solid waste (ENCORE 2020). In this example, direct impacts on biodiversity could occur through converting habitats for crop production. Indirect impacts could occur in downstream areas when water is abstracted from natural sources and used for crop production. Cumulative impacts could occur through pollutants; even if the pollution from a single fiber producer is minimal, when combined with the pollution from other producers and industries operating in the landscape, there could be substantial negative impacts on sensitive species.

Dependencies

The ecosystem services provided by natural capital stocks, such as clean air and water, healthy soils, and raw materials, are ultimately the basis of all economic activity. Biodiversity underpins many of these ecosystem services. More than half of global gross domestic product (GDP) is highly or moderately dependent on nature, with business activities depending heavily on nature both in direct operations and in supply chains (WEF 2020a).

In the Protocol, a dependency is material if consideration of its value, as part of the set of information used for decision-making, has the potential to alter that decision. Some business activities have material dependencies on the presence of aspects of biodiversity, such as species or habitats. For example, the natural rubber industry depends on sap collected from specific species of tree. In contrast, some production processes depend on the diversity of habitats or species. For example, agricultural crops depend on a diverse range of animal pollinators for benefits such as being able to grow crops requiring pollination by different species, and being able to grow crops throughout the year when different pollinator species are active.

b. Business risks and opportunities

Natural capital thinking provides businesses and financial institutions with a more detailed understanding of the significance of impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and other aspects of the environment by framing them as risks and opportunities. This can strengthen your business’s consideration of interconnections and trade-offs between different environmental, social, and economic issues, leading to more informed decision-making. For financial institutions, understanding the value of impacts and dependencies on biodiversity leads to better insight on the magnitude, reliability, and resilience of financial returns, due to biodiversity’s role in supporting delivery of ecosystem services.

Risks

Biodiversity loss can pose direct risks to your business operations where you have dependencies on the goods and services that biodiversity generates, either directly and/or within supply chains. The risk of disruption will continue to intensify if biodiversity continues to be lost.

In many instances, the majority of the benefits from biodiversity are received by society rather than directly by your business. As a result, where your business activities (or the activities of businesses in your financial portfolio) impact on biodiversity, you face risks associated with societal relationships, reputation, marketing, laws, regulations, and access to finance.

Reputational risks to business are increasing as biodiversity continues to decline, and as pressure from consumers to slow and reverse this decline continues to grow. For example, impacts on charismatic species affect societies who place value upon them for cultural, ethical, and/or philosophical reasons. Threats to these species resulting from business operations can create reputational risks for business. For example, clearing rainforest habitats to grow oil palm may destroy the habitat of the orangutan, a culturally important species. Including societal values in the scope of a business’s natural capital assessment is therefore needed to identify reputational risks.

Financial institutions are exposed to multiple types of biodiversity-related risk, including risk of default by clients, lower returns from investees, and increasing insurance liabilities. Understanding the contribution of biodiversity enhances understanding of natural capital risks across your portfolio, enabling more informed risk management decisions. Financial institutions can turn risks into opportunities by managing investments sustainably to mitigate impacts on biodiversity (UNEP et al. 2020). An investment manager, for example, could promote sustainable land use practices that result in positive biodiversity and socioeconomic impacts through blended finance (where public money is used to increase private investment in projects that can have positive development while producing financial returns).

It is important that you apply a broad approach to natural capital assessments that considers the multiple ways in which biodiversity has value to different stakeholders. You should carry out assessments over a suitable scale and time period for your impacts to be identified, including impacts that accumulate over time, and direct and indirect impacts (e.g., overexploitation of resources, habitat loss, contributions to climate change), as well as impacts that occur as a result of the interaction of activities of different organizations operating in a landscape (cumulative impacts).

- For example, the contribution of a farm’s pesticide use could add to the cumulative impacts of surrounding farms, which in aggregate can affect the ecosystem’s predator-prey balance, risking future pest outbreaks or a decline in access to wild pollinators and associated pollination services.

- Another example is overfishing. Overfishing can reduce fish biomass, affecting marine biodiversity and the sustainability of fisheries (Sumaila et al. 2020). In the case of the North Atlantic cod stock, this resulted in the collapse of six populations of cod leading to a moratorium where fishers were no longer allowed to harvest the species (Myers et al. 1997, Pederson et al. 2017).

Inclusion of cumulative impacts in the scope of a business’s natural capital assessment is important to ensure risks such as declining fish stocks, future crop losses, or increased pest control costs can be mitigated.

Finally, biodiverse ecosystems are more resilient to unpredicted changes. In the example of a tropical island experiencing a greater number of cyclones over a five-year period due to climate change, an island with a greater number of tree species of different heights, with the roots reaching to varying depths, is more likely to be able to withstand high wind speeds with minimal damage. An island covered with a single species of tall trees, however, is more likely to experience damage, and a lengthened recovery period. For this reason, biodiverse natural surroundings are better able to mitigate against unpredictable weather events. Biologically diverse communities are more likely to contain species that confer resilience of that ecosystem to change. As a community accumulates species, there is a higher chance of any of them having traits that enable them to adapt to a changing environment (Cleland 2011).

Click here to see how a fashion company has integrated biodiversity as part of a natural capital assessment to identify risks in their operations and supply chain.

Opportunities

Understanding biodiversity as an integral part of natural capital stocks, as well as its role in underpinning the goods and services that stocks generate, allows you to identify and manage potential new business opportunities, business models that are viable in the long term, cost savings, and increases in operational efficiency. If your business is able to demonstrate minimal impacts, or biodiversity enhancements, you are likely to secure benefits such as preferential access to resources and financing, better relationships with stakeholders, maintaining a social license to operate, and retaining employees. For example, adopting sustainable fishing practices to prevent overfishing would require a reduction in the number of catches made annually and result in a reduction in short-term profit. However it would better ensure sustainability of resources and a maintained social license to operate in the long term. This is especially true in the case of fishing companies who have a high impact on fisheries in their catchment area and local communities.

Click here to see how a financial institution has integrated biodiversity as part of a natural capital assessment to identify opportunities for sustainable and socially responsible investment.

Business models and activities that promote biodiversity can present an opportunity for enhancement of natural capital stocks. Examples of these activities include implementing regenerative agriculture to reduce fertilizer costs, or adopting nature-based solutions to increase resilience to natural disasters. In both cases these activities would offer sustainable opportunities for benefits to a business while enhancing natural capital stocks, with resulting benefits for wider society.

Financial institutions can make investment decisions based on impacts and dependencies on biodiversity, and therefore realize reputational benefits while reducing risks within a portfolio.

Further examples of potential business risks and opportunities relating to biodiversity are provided in table 1.2.

Category | Risk example | Opportunity example |

| Operational Regular business activities, expenditures, and processes | Overexploitation in an important fishery has caused depletion of fish stocks. The reduction in fish population has had a cascading effect through the ecosystem, leading to conditions that are no longer suitable for development of juveniles. The fishing industry has collapsed, with knock-on implications for fishers, processing plants, distributors, and seafood retailers. | Climate change threatens to reduce the dry-season water supply to a hydroelectric dam. The energy company operating the dam has adopted a nature-based solution through funding restoration of wetlands high in the watershed with diverse native vegetation in order to increase water storage. This is expected to improve the reliability of downstream water flows throughout the year, despite climate uncertainty. |

| Legal and regulatory Laws, public policies, and regulations that affect business performance | A chemical used in pesticides is harmful to bees and other insects that pollinate agricultural crops. New laws have been brought in banning its use. Agrochemical companies that were using the chemical are no longer able to manufacture and sell several of their products. | A major supermarket is supporting new legislation to reduce use of single-use plastics in food packaging, due to concerns about impacts on marine biodiversity. The supermarket already exclusively uses suppliers who minimize single-use plastics in their packaging. Therefore, this legislation will give an advantage over competing supermarkets who have not adapted their approach to packaging. |

| Financing Costs of, and access to, capital including debt and equity | A mining company is seeking investment to expand its operations in a mineral-rich forest. The forest has high biodiversity value and supports the livelihoods of local communities by providing services such as food, fuel, and water. The company lacks systematic information on their impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Financial organizations are unwilling to lend to or invest in the company as risks are unknown. | A small forestry company has become the first operator in a developing country to receive environmental certification. These environmental credentials have enabled the company to access a long-term loan to monitor and report on their sustainable forestry practices, and make investments to improve the efficiency of forestry management. |

| Reputational and marketing Company trust and relationships with direct business stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and employees

| A multinational oil company has suffered a spill around an offshore drilling rig, causing extensive damage to surrounding ecosystems and mass mortality of seabirds and turtles. Public and investor confidence has fallen rapidly, with the company seeing a huge reduction in market value. | For the first year following release of a new range of products, a cosmetics company is donating part of their income from each purchase to a biodiversity conservation project focused on protecting habitat for a charismatic eagle. Through linking the product range to this culturally important species the company are expecting to attract new customers into their stores. |

| Societal Relationships with the wider society (e.g., local communities, NGOs, government agencies, and other stakeholders)

| A development bank is supporting a road-building project through a remote area of tropical forest. The biodiversity impacts of this project are expected to be negative, particularly for large mammals which are harvested by local communities for food and rituals. The bank is under pressure from an alliance of international NGOs and local communities to abandon the project. | A water company has restored habitat for wetland bird species around the margins of one of its reservoirs. The area is now well used by both local and more distant visitors for nature-based recreation, benefiting the company’s public image and stakeholder relationships. |

*The typology of risks and opportunities in table 1.2 is the same as in the Natural Capital Protocol. Other similar typologies are also used, such as the biodiversity-related financial risk categories in the “Nature is too big to fail” report (PwC & WWF 2020).

Company example: Supply chain (fashion industry)Kering S.A. has developed an Environmental Profit and Loss (EP&L) accounting methodology for measuring and quantifying the impacts of its activities on natural capital. The methodology aims to capture both the impacts of the Group’s direct operations and those of its supply chain. The methodology measures carbon emissions, water consumption, air and water pollution, land use, and waste production. These impacts are converted into monetary values for comparison and use in guiding sustainability decisions (Kering 2013)

Ecosystem services supported by biodiversity sit at the base of the supply chain for many of Kering’s products. The EP&L has a broad scope, and although it does not quantify biodiversity as a separate indicator, many of the impacts that it seeks to manage have consequences for biodiversity. Impacts on biodiversity are included in the methodology primarily through indicators of land-use change, which take into account areas of habitats (such as tropical forests, wetlands, etc.) that have been converted for different production systems, and the associated reduction in the value of ecosystem services. Specifically, to estimate the impact on ecosystem services, the EP&L looks at three indicators: above-ground biomass, species richness, and soil organic carbon (the latter is a strong proxy for overall soil health).

Kering’s methodology is continually evolving, and more explicit integration of impacts on biodiversity is a key priority for the organization. Given that it is not appropriate or possible to place an economic value on all aspects of biodiversity, Kering is exploring separate biodiversity indicators to sit alongside and complement the EP&L (CISL 2020; CISL 2016).

To date, application of the methodology has provided insights and increased transparency around the environmental impacts of different aspects of Kering’s business. For example, it has revealed that the majority of impacts lie in their supply chain. This has enabled Kering to prioritize strategies that can lead to improved environmental outcomes, such as regenerative agriculture in the production of raw materials. By integrating biodiversity as part of the methodology, Kering will be able to identify and implement actions to reduce biodiversity impacts, hence reducing the risk of disruption to their supply chains.

Kering S.A. has developed an Environmental Profit and Loss (EP&L) accounting methodology for measuring and quantifying the impacts of its activities on natural capital. The methodology aims to capture both the impacts of the Group’s direct operations and those of its supply chain. The methodology measures carbon emissions, water consumption, air and water pollution, land use, and waste production. These impacts are converted into monetary values for comparison and use in guiding sustainability decisions (Kering 2013)

Ecosystem services supported by biodiversity sit at the base of the supply chain for many of Kering’s products. The EP&L has a broad scope, and although it does not quantify biodiversity as a separate indicator, many of the impacts that it seeks to manage have consequences for biodiversity. Impacts on biodiversity are included in the methodology primarily through indicators of land-use change, which take into account areas of habitats (such as tropical forests, wetlands, etc.) that have been converted for different production systems, and the associated reduction in the value of ecosystem services. Specifically, to estimate the impact on ecosystem services, the EP&L looks at three indicators: above-ground biomass, species richness, and soil organic carbon (the latter is a strong proxy for overall soil health).

Kering’s methodology is continually evolving, and more explicit integration of impacts on biodiversity is a key priority for the organization. Given that it is not appropriate or possible to place an economic value on all aspects of biodiversity, Kering is exploring separate biodiversity indicators to sit alongside and complement the EP&L (CISL 2020; CISL 2016).

To date, application of the methodology has provided insights and increased transparency around the environmental impacts of different aspects of Kering’s business. For example, it has revealed that the majority of impacts lie in their supply chain. This has enabled Kering to prioritize strategies that can lead to improved environmental outcomes, such as regenerative agriculture in the production of raw materials. By integrating biodiversity as part of the methodology, Kering will be able to identify and implement actions to reduce biodiversity impacts, hence reducing the risk of disruption to their supply chains.

Company example: FinanceASN Bank is a finance organization committed to sustainable and socially responsible investment. Using natural capital thinking they have developed ambitious, long-term goals associated with a three pillar sustainability framework: climate change, biodiversity, and human rights. Consistent with their natural capital approach, ASN Bank sees important interconnections between these three pillars, for example they recognize that investing in biodiversity can also create benefits associated with mitigating climate change and human rights.

ASN Bank acknowledges that their operations might be contributing to the loss of biodiversity. Their goal is to reverse this, where “all investments and loans of ASN Bank result in a net positive effect on biodiversity in 2030.” To assess progress against this goal, they need to be able to measure their biodiversity impacts. They have developed a methodology for calculating the biodiversity footprint of their loans and investments, which was first applied in 2014 and subsequently refined in annual assessments. Insights from this assessment can be used to tailor ASN Bank’s investment portfolio to its long-term biodiversity goal, through identifying “impact hotspots” (risks), and sectors and investments that will have a positive impact on biodiversity (opportunities).

Furthermore, ASN Bank are planning to establish a Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials initiative (PBAF), which aims to bring together financial institutions to develop and refine methodologies for biodiversity footprinting. This will draw upon the bank’s experience of establishing and running a similar initiative for assessing greenhouse gas emissions, the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), which is a global initiative adopted by 50+ financial institutions.

ASN Bank is a finance organization committed to sustainable and socially responsible investment. Using natural capital thinking they have developed ambitious, long-term goals associated with a three pillar sustainability framework: climate change, biodiversity, and human rights. Consistent with their natural capital approach, ASN Bank sees important interconnections between these three pillars, for example they recognize that investing in biodiversity can also create benefits associated with mitigating climate change and human rights.

ASN Bank acknowledges that their operations might be contributing to the loss of biodiversity. Their goal is to reverse this, where “all investments and loans of ASN Bank result in a net positive effect on biodiversity in 2030.” To assess progress against this goal, they need to be able to measure their biodiversity impacts. They have developed a methodology for calculating the biodiversity footprint of their loans and investments, which was first applied in 2014 and subsequently refined in annual assessments. Insights from this assessment can be used to tailor ASN Bank’s investment portfolio to its long-term biodiversity goal, through identifying “impact hotspots” (risks), and sectors and investments that will have a positive impact on biodiversity (opportunities).

Furthermore, ASN Bank are planning to establish a Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financials initiative (PBAF), which aims to bring together financial institutions to develop and refine methodologies for biodiversity footprinting. This will draw upon the bank’s experience of establishing and running a similar initiative for assessing greenhouse gas emissions, the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), which is a global initiative adopted by 50+ financial institutions.