Explore the resources below to assist in completing this action.

Biodiversity Guidance action 3.2.5

3.2.5 Decide which types of value you will consider

The Protocol outlines how valuation involves a continuum of qualitative, quantitative, and monetary approaches, and describes key features of each approach. It also suggests key considerations when determining which type of valuation is most appropriate to meet your objectives. Valuing natural capital often involves valuing the final benefits that people/businesses receive from natural capital. If biodiversity contributes to these final benefits, but is not explicitly considered as part of them, its contribution or necessity may not be visible in your assessment. It is important to assess how identified benefits rely on the underlying biodiversity stock, and ensure the ramifications for maintaining the condition of biodiversity are considered alongside valuation results. If biodiversity is not visible or not captured in your valuation process, its importance can be underappreciated. Your organization will not have a full picture of how risks and opportunities can manifest and may therefore make decisions based on incomplete information (for more information see Framing Guidance action 1.2.1 on “Why are some of these values often underappreciated in natural capital assessments?”).

Before proceeding with your valuation, you should be aware of, and find ways to address, potential concerns that generate opposition to valuing biodiversity, especially in monetary units. Concerns may include, but will not be limited to, fears around the “commodification” of nature and the risk that bringing nature closer to the economic system will detract from societal responsibilities to protect biodiversity. You should also recognize that it is both inappropriate and impossible to accurately quantify the intrinsic worth of biodiversity in monetary units, and you should find alternative ways to consider biodiversity’s intrinsic value in your decision-making. It is important that you present the approach taken, the aspects of biodiversity’s value included, and the assumptions made clearly alongside your results. This will help to avoid a well-intended assessment from being taken out of context or otherwise misunderstood.

Monetary valuation can be used to understand the magnitude and relevance of costs and benefits associated with your impacts and dependencies on biodiversity. Monetary valuation summarizes information in a common and tractable unit, making it easier for you to communicate with key stakeholders and assess trade-offs.

Before undertaking monetary valuation however, you should consider whether this is the appropriate approach. In the following circumstances you should not use monetary techniques (adapted from TEEB 2010):

- When you cannot estimate accurate values;

- When it can be considered morally inappropriate (e.g., placing a monetary value on an intrinsically/culturally valuable area to the surrounding communities) (Synder et al. 2003);

- When a large-scale change in biodiversity is taking place (e.g., when a large proportion of a remaining population or habitat is affected);

- When an irreversible change is expected.

Other factors that you should consider when deciding whether to use a monetary technique include the nature of your decision, the target audience, and the availability of data to support conversion to monetary units. Qualitative and quantitative techniques can be applied to values that cannot be assessed with monetary techniques.

For further information about qualitative, quantitative, and monetary valuation approaches, see Measuring and Valuing Guidance action 7.2.3.

Biodiversity Guidance action 1.2.1

1.2.1 Familiarize yourself with the basic concepts of natural capital [and biodiversity]

a. What is biodiversity and how does it relate to natural capital?

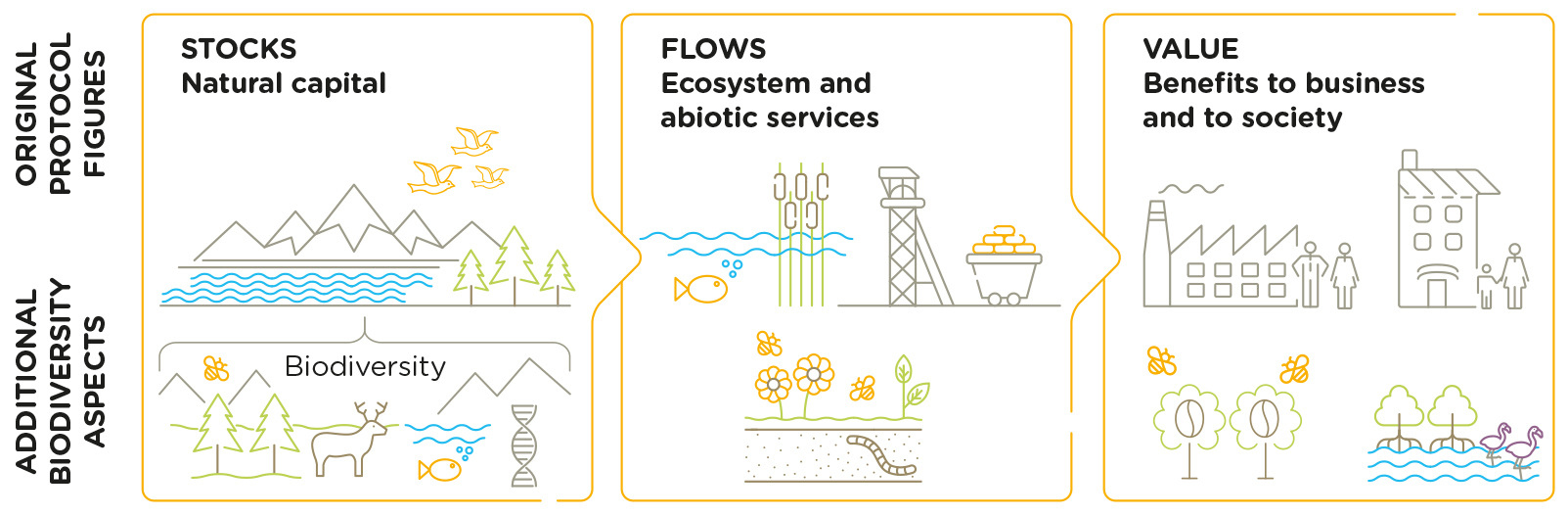

Natural capital is a concept used for describing our relationship with nature. The presence of, and interactions between, natural capital stocks generates a flow of goods and services. These goods and services create value through the benefits they provide to business and society (Natural Capital Coalition 2016).

The flows of benefits from ecosystems to people are often described as ecosystem services (MA 2005). Ecosystem services result from ecosystem function, which describes the flow of energy and materials through ecosystems (IPBES 2019), and is the process by which ecosystems maintain their integrity (MA 2005).

Businesses and financial institutions often already evaluate environmental risk from specific issue perspectives (e.g., energy use, waste, pollution, climate change, natural resource use, and biodiversity). Natural capital encompasses all of these environmental issues and helps to describe how they are interrelated. The application of a natural capital approach builds on the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and risk initiatives already in use, providing additional benefits such as understanding these as a set of interrelated issues with trade-offs.

So where does biodiversity come in? Biodiversity plays an integral role, underpinning the goods and services that natural capital stocks generate (figure 1.1).

Biodiversity describes the variety of life and is the living component of what can be thought of as natural capital stocks. It plays an important role in the provision of the services we receive from nature. Biodiversity can refer to the level of genetic variation, the variety of species present, or the variety of groups of species or ecosystems. In general, more biodiversity equates to a higher quantity, quality, and resilience of ecosystems and the services they provide, which underpin the benefits to business and society. As such biodiversity can be an indicator of the condition and resilience of natural capital stocks. It also contributes benefits to business and society in its own right, for example through direct and intrinsic value of species, nature-based solutions, and by enriching other benefits such as nature-based recreation.

Figure 1.1 expands on figure 1.1 in the Protocol to illustrate how biodiversity underpins healthy natural capital stocks. The figure provides further examples of biodiverse ecosystem service flows and highlights how biodiversity underpins the value flowing to business and society using the examples of pollinators providing benefits to a coffee production business and mangroves/flamingos providing flood mitigation/wildlife viewing for society.

Biodiversity is in unprecedented decline on a global scale. The rate of species extinction is already tens to hundreds of times higher than in the past and is increasing. The majority of natural ecosystems are deteriorating or have been destroyed. For example, over 85% of wetland habitats present in 1700 had been lost by 2000 (IPBES 2019).

Biodiversity’s decline has important negative implications for business and society. The current rate of loss exceeds a planetary boundary (Steffen et al. 2015) meaning that it poses a high risk of deleterious or even catastrophic environmental change. Biodiversity loss will prevent us from achieving international objectives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (UN 2015) and is considered to be one of the greatest risks facing humanity on a global scale, in terms of both likelihood of occurring and the potential magnitude of negative impact (WEF 2020b).

There is an important and complex relationship between biodiversity and the delivery of ecosystem services. In many cases, biodiversity affects the quantity, quality, and resilience of the goods and services delivered from natural capital stocks:

- Quantity: More biodiversity, in general, has the potential to deliver a greater number of ecosystem services to a wider range of beneficiaries. For example, a biodiverse woodland may have high cultural and recreational values, deliver regulating services like water filtration, soil stabilization, and carbon sequestration, and be sustainably harvested for timber. In comparison, a plantation woodland made up of a small number of species might only provide timber and some regulating services.

- Quality: In many instances, biodiversity is linked with the quality of ecosystem service delivery. For example, a plantation woodland is likely to provide a lower level of ecosystem services such as water filtration, soil stabilization, and carbon sequestration than a biodiverse woodland.

- Resilience: Biodiversity also contributes to the resilience of natural capital stocks and the stability of ecosystem service provision. For example, biodiverse coral reefs (which contribute to ecosystem services such as maintaining fish stocks and defending coastlines against storms and erosion) are more resilient to changes in ocean temperature. The variety and genetic diversity of species and ecosystems present affects the ability of a reef to resist and adapt to the effects of climate change and other disturbances.

Thinking about it in this way, you can broadly equate the benefits of biodiversity to the benefits of a diverse portfolio of financial stock. The more diverse the stock, the greater the spread of risk.

See box 1.1 for frequently asked questions about biodiversity and natural capital.

Box 1.1: Frequently asked questionsIs biodiversity the same as natural capital?

No. Natural capital refers to a stock of living and non-living components that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people. Biodiversity refers to the variety within the living components of this stock, and can be seen as an indicator of its condition.

Is biodiversity just about threatened species and protected areas?

No. The term biodiversity applies to the variety of all living organisms. Threat status or delineation as a protected area are specific designations granted to species or habitats that are considered important or threatened, to support their conservation. However, taking account of all components of biodiversity is challenging, so threatened species, protected areas, and other measures of the area and integrity of ecosystems are often used when attempting to measure biodiversity.

How does biodiversity relate to ecosystem services?

Ecosystem services are provided by the presence and interactions of natural capital stocks. Biodiversity forms a fundamental part of natural capital stocks and their ability to deliver goods and services to business and society. In many cases, the relationship between biodiversity and the goods and services produced is complex. In general, more biodiversity equates to a higher quantity, quality, and resilience of ecosystem service provision. Less biodiverse natural systems can still yield ecosystem goods and services but they are generally fewer, of lower quality, and more vulnerable to change.

I have included ecosystem services in my natural capital assessment. Doesn’t that mean I’ve automatically included biodiversity?

No. Ecosystem services are flows of goods and services, while biodiversity refers to the variety of the living component of a natural capital stock. Natural capital assessments that focus only on the flow of benefits (ecosystem services) rather than the condition of the stock (biodiversity) can lead to poor business decisions. For example, a sole focus on ecosystem services could lead to investments in maximizing highly valued flows in the short-term while stocks are left to deteriorate. Biodiversity’s contribution to ecosystem services is complex, and often poorly understood. Natural capital assessments need to explicitly include biodiversity as the stock that generates benefits.

Is biodiversity the same as natural capital?

No. Natural capital refers to a stock of living and non-living components that combine to yield a flow of benefits to people. Biodiversity refers to the variety within the living components of this stock, and can be seen as an indicator of its condition.

Is biodiversity just about threatened species and protected areas?

No. The term biodiversity applies to the variety of all living organisms. Threat status or delineation as a protected area are specific designations granted to species or habitats that are considered important or threatened, to support their conservation. However, taking account of all components of biodiversity is challenging, so threatened species, protected areas, and other measures of the area and integrity of ecosystems are often used when attempting to measure biodiversity.

How does biodiversity relate to ecosystem services?

Ecosystem services are provided by the presence and interactions of natural capital stocks. Biodiversity forms a fundamental part of natural capital stocks and their ability to deliver goods and services to business and society. In many cases, the relationship between biodiversity and the goods and services produced is complex. In general, more biodiversity equates to a higher quantity, quality, and resilience of ecosystem service provision. Less biodiverse natural systems can still yield ecosystem goods and services but they are generally fewer, of lower quality, and more vulnerable to change.

I have included ecosystem services in my natural capital assessment. Doesn’t that mean I’ve automatically included biodiversity?

No. Ecosystem services are flows of goods and services, while biodiversity refers to the variety of the living component of a natural capital stock. Natural capital assessments that focus only on the flow of benefits (ecosystem services) rather than the condition of the stock (biodiversity) can lead to poor business decisions. For example, a sole focus on ecosystem services could lead to investments in maximizing highly valued flows in the short-term while stocks are left to deteriorate. Biodiversity’s contribution to ecosystem services is complex, and often poorly understood. Natural capital assessments need to explicitly include biodiversity as the stock that generates benefits.

b. What are the values of biodiversity?

Despite the benefits biodiversity provides to business and society, many of its values are often underappreciated in natural capital assessments (see box 1.2 for more discussion of value).

The values of biodiversity can be summarized as follows:

- Direct value: In some instances, biodiversity itself has value to business’s bottom line, for example through providing food, or in tourism based on wildlife watching.

- Underpinning value: More commonly, biodiversity has value through its role in the delivery of ecosystem services. Systems such as water cycles, carbon cycles, and crop production rely on the interactions of living things, and the diversity of these living things will influence the quantity and quality of the services delivered.

- Insurance and options value: Some goods and services can be delivered with relatively low biodiversity, but are vulnerable to change from factors such as pests, diseases, or climatic instability. Biodiversity increases the resilience of a system, enabling it to continue providing ecosystem services despite changes in conditions that may occur in the future, which are often uncertain. Biodiversity provides options for delivery of ecosystem services from alternative sources in the future (for example new crop species that might be domesticated for agriculture or new medicines). Biodiversity also provides options for new ecosystem services, for example benefits from biodiversity that are not yet recognized (i.e., where biodiversity is currently providing benefits to business and/or society that we are not yet aware of) or services that will only become beneficial in the context of future technological or societal innovations (i.e., where biodiversity contributes to processes that are not currently beneficial but become beneficial due to future changes to the natural environment or changes to the way people live or what they value).

- Intrinsic value: Biodiversity has value independent of human use of the goods and services it provides. This value is associated with the moral right of living things to exist. Some people consider intrinsic biodiversity values to also be intertwined with other values, such as bequest value (knowing that future generations will continue to benefit from biodiversity), altruist value (knowing that other people of the same generation can benefit from biodiversity), and existence value (connected to our desire to protect biodiversity irrespective of whether we derive any value from it other than associated with our knowledge of its existence).

You may also come across the terms “use value” and “non-use value” to describe and categorize biodiversity values. Use values encompass the direct values, underpinning values (also sometimes called indirect values), and insurance and options values outlined above. Non-use values relate to biodiversity’s intrinsic value, bequest value, altruist value, and existence value (TEEB 2010).

The relevance of biodiversity to your business relates to both the values it provides to your business and the value of biodiversity to wider society. Often, the value of biodiversity will be realized from the perspective of wider society, rather than solely for your business.

Box 1.2: What is meant by value?In the Protocol, value is defined as the importance, worth, or usefulness of something (Natural Capital Coalition 2016).

The concept of value represents what something is worth to someone. Biodiversity may have different values to different groups of people, and the value of biodiversity may be different from a business perspective and from a societal perspective.

Value is not the same as cost or price. Cost represents the amount incurred through an action (or lack of action), while price is the amount paid for something (Olajide et al. 2016).

Valuation is the process of estimating the relative importance, worth, or usefulness of natural capital to people (or to a business), in a particular context. Valuation may involve qualitative, quantitative, or monetary approaches, or a combination of these (Natural Capital Coalition 2016). See the Valuing Guidance for further information on valuing biodiversity as part of your natural capital assessment.

In the Protocol, value is defined as the importance, worth, or usefulness of something (Natural Capital Coalition 2016).

The concept of value represents what something is worth to someone. Biodiversity may have different values to different groups of people, and the value of biodiversity may be different from a business perspective and from a societal perspective.

Value is not the same as cost or price. Cost represents the amount incurred through an action (or lack of action), while price is the amount paid for something (Olajide et al. 2016).

Valuation is the process of estimating the relative importance, worth, or usefulness of natural capital to people (or to a business), in a particular context. Valuation may involve qualitative, quantitative, or monetary approaches, or a combination of these (Natural Capital Coalition 2016). See the Valuing Guidance for further information on valuing biodiversity as part of your natural capital assessment.

c. Why are some of these values often underappreciated in natural capital assessments?

The full value of biodiversity may be overlooked in your natural capital assessment if links have not been identified between your business activities and biodiversity. For example, your business might depend on water extracted from a natural water source, and the quality and quantity of water available might be affected by biodiversity in the upstream watershed. This link between biodiversity and delivery of water needs to be recognized to identify and include the value of this business dependency on biodiversity within your natural capital assessment. Furthermore, your business may not have identified all impacts on biodiversity. For example, abstraction of water may have impacts on species in downstream wetland areas, and these impacts cannot be included in your natural capital assessment if they have not been identified.

Another reason why biodiversity might be underappreciated is due to the multitude of different components (e.g., species, habitats, ecosystems, genes) that make up biodiversity, and upon which your business might have impacts and/or dependencies. For example, the impacts of your business activities on some species might be minimal, however other species might be more sensitive. Lack of knowledge and understanding associated with these different components of biodiversity, and the interactions between them, may lead to underappreciation of some biodiversity values in natural capital assessments.

In addition, the Protocol focuses primarily on flows of ecosystem services from natural capital, and their value to business and society. Capturing flows is important, however the full contribution of biodiversity to the quantity, quality, and resilience of ecosystem service delivery can be unclear when using this approach (CCI 2016, Mace 2019). The biodiversity values likely to be underappreciated when focusing on flows of benefits are outlined below.

- Underpinning value: By focusing on flows of final benefits, assessments may fail to recognize the role of biodiversity in delivery of ecosystem services. Recognizing this underpinning value can be challenged by the difficulty of untangling the specific contribution of biodiversity to ecosystem service delivery, particularly given time lags between the loss of biodiversity and the decline in delivery of goods and services. Furthermore, underpinning value can be underappreciated where biodiversity contributes to goods and services that we are unable to measure, or may even fail to recognize as providing us with benefits in the first place.

- Insurance and options value: By focusing on flows of immediate and tangible benefits, natural capital assessments may overlook future benefits that biodiversity could provide. These benefits could include biodiversity’s role in providing a stable and resilient flow of ecosystem services under changing environmental conditions (insurance value), and/or delivering other benefits in the future that may not yet be known, such as new medicines, materials, or crops (options value).

- Intrinsic value: Biodiversity’s intrinsic value is independent of any use of goods and services by people and therefore will be overlooked when focusing on ecosystem service flows.

Better recognition of the importance of biodiversity can be achieved through improvements in assessment methodologies. However, it is important to recognize that gaps will remain and some values will continue to be underappreciated. For example, this may be due to limitations in scientific understanding of the relationships between biodiversity and delivery of goods and services. You should usually consider the values of biodiversity identified in a natural capital assessment as minimum estimates and take a precautionary approach in business decision-making, considering biodiversity values alongside other information and in consultation with stakeholders.

Biodiversity Guidance action 7.2.3

7.2.3 Select appropriate valuation technique(s)

You can use valuation to understand the importance of biodiversity in a particular context. A variety of approaches are available. When selecting an approach, you must understand its applicability and limitations.

Your choice of valuation technique will depend on whether you want to estimate qualitative, quantitative, or monetary values for biodiversity:

- Qualitative values inform the scale of costs and benefits in non-numerical terms.

- Quantitative values use numerical data as indicators of costs and benefits.

- Monetary values translate costs and benefits into a common currency.

Different types of values offer different ways to examine the consequences of your impacts and dependencies on biodiversity. Hybrid approaches involve using different types of value (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, and/or monetary) in combination to assist your decision-making. You may find hybrid approaches particularly helpful for ensuring that both of the following values are captured in your assessment: 1) the value of biodiversity as part of a natural capital stock underlying continued provision of benefits; 2) the value of the final benefits provided by biodiversity.

You may find it easier to measure the condition of biodiversity (as part of a natural capital stock) in biophysical units, such as the number of individuals of a species or the area of a habitat. If you wish to progress to valuation, you could then convert measurements into qualitative, quantitative, or monetary values. For example, expressing the number of individuals of a species at a site (measurement) as a proportion of the total population could give a quantitative indication of the biodiversity value of the site.

It can be challenging to place monetary values on biodiversity stocks. It is often more straightforward to apply monetary valuation techniques to the goods and services flowing from biodiversity (i.e., the value of the final benefits provided by biodiversity). For example, you could value the benefits provided by wild pollinators using market prices for crops.

Even where monetary valuation is your ultimate goal, you may only be able to convert some aspects of biodiversity’s value to monetary units. Qualitative and/or quantitative approaches can be applied to aspects of biodiversity’s value that cannot be assessed with monetary techniques. For example, you could apply qualitative approaches to spiritual values associated with biodiversity, and/or might use quantitative values to understand health benefits associated with biodiversity.

You may wish to apply a sequential approach where you first estimate values qualitatively and/or in quantitative units, and then convert them into monetary values (TEEB 2010). You can develop biodiversity values over several iterations. For example, in initial valuation analysis with limited scope you may estimate qualitative values, and then convert progressively more values to monetary units in subsequent assessments with increasing complexity and assumptions.

a. Qualitative and quantitative valuation techniques

The qualitative and quantitative valuation techniques described in the Protocol can be applied to estimating values for biodiversity (box 7.1). The advantages and disadvantages of applying different techniques to biodiversity are the same as for other aspects of natural capital. Therefore, you are encouraged to look at the Protocol for information about valuing biodiversity using qualitative or quantitative techniques. Note that while this Guidance only provides further biodiversity-specific information about monetary valuation techniques, qualitative and quantitative techniques are often more appropriate for capturing some aspects of biodiversity’s value.

Box 7.1: The UK National Ecosystem AssessmentThe United Kingdom’s National Ecosystem Assessment (UK NEA) provides an example of how non-monetary valuation techniques can be used to consider biodiversity’s value alongside monetary values. In this assessment, impacts on farmland bird species and bird diversity were valued using multi-criteria analysis (MCA; refer to the Protocol table 7.1 for more information on this and other valuation techniques). Monetary valuation techniques were applied to other impact drivers such as agricultural output, greenhouse gas emissions, as well as to recreation and urban greenspace under different scenarios (Bateman et al. 2011). The different types of value could then be considered in parallel in decision-making—this is therefore also an example of a hybrid approach.

The NEA synthesis report shows how this hybrid approach has been applied and a study by Defra (UK, Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) also highlights the difficulty of assessing cultural goods though monetary techniques alone, emphasizing the importance of recognizing their values using a range of techniques, such as MCA. The collective value of biodiversity and ecosystem services requires a hybrid approach, using both quantitative and qualitative techniques (UK NEA 2011). Businesses would be able to apply this approach to integrate both the values of biodiversity stocks and final benefits when undertaking natural capital assessments.

The United Kingdom’s National Ecosystem Assessment (UK NEA) provides an example of how non-monetary valuation techniques can be used to consider biodiversity’s value alongside monetary values. In this assessment, impacts on farmland bird species and bird diversity were valued using multi-criteria analysis (MCA; refer to the Protocol table 7.1 for more information on this and other valuation techniques). Monetary valuation techniques were applied to other impact drivers such as agricultural output, greenhouse gas emissions, as well as to recreation and urban greenspace under different scenarios (Bateman et al. 2011). The different types of value could then be considered in parallel in decision-making—this is therefore also an example of a hybrid approach.

The NEA synthesis report shows how this hybrid approach has been applied and a study by Defra (UK, Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) also highlights the difficulty of assessing cultural goods though monetary techniques alone, emphasizing the importance of recognizing their values using a range of techniques, such as MCA. The collective value of biodiversity and ecosystem services requires a hybrid approach, using both quantitative and qualitative techniques (UK NEA 2011). Businesses would be able to apply this approach to integrate both the values of biodiversity stocks and final benefits when undertaking natural capital assessments.

b. Monetary valuation techniques

Monetary valuation allows you to compare costs and benefits in a single, readily understood unit. It can simplify the assessment of trade-offs, not only incorporating biodiversity values, but also other environmental, social, and economic considerations.

The valuation techniques included in this Guidance are the same as those already included in the Protocol, but there are some additional considerations that you should take into account when selecting a technique to apply to biodiversity.

Table 7.1 in this Guidance outlines key biodiversity-specific considerations for each technique. Note that this table builds on table 7.1 in the Protocol, which should be read alongside it. Table 7.1 in the Protocol provides a description of each technique, and an indication of the data requirements, duration, budget, skills required for application, and advantages and disadvantages in the general context of natural capital.

Table 7.1 below provides you with information on the benefits and limitations of each technique in the context of biodiversity, including what type of biodiversity values it can capture and whether it captures impacts and/or dependencies on biodiversity. Table 7.1 also provides examples of how each technique can be used to estimate biodiversity values.

Refer to the Framing Guidance action 1.2.1 (B) for more information on the different types of values used in table 7.1.

Monetary valuation technique | Biodiversity considerations* | |

|---|---|---|

Market and financial prices | Benefits: Well-suited to identifying and valuing final benefits provided by biodiversity. Limitations: The extent to which the value of biodiversity is captured is heavily dependent on the degree to which variation in biodiversity influences demand for the market good. Biodiversity values: Direct, some underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Both Examples of use: The market price of an agricultural output could be used to value an expected increase in crop yield associated with interventions to increase wild pollinator populations accessing a plantation. Previous studies have been used to make the case for biodiversity-positive investments to protect and increase pollinator populations given their direct potential to influence the quality and quantity of the crop that is produced. | |

Production function (change in production) | Benefits: Can be used to assess the value of complex and unclear business dependencies on biodiversity. Limitations: Requires complex modeling which may introduce a high level of uncertainty. Biodiversity values: Underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Dependencies Examples of use: More diverse forests tend to absorb and store more carbon. The increase that is derived from biodiversity in the carbon value of a forest may be estimated using production function modeling. Businesses looking to invest in forests as part of their climate mitigation and adaptation strategies can use this approach to understand their options, and to seek investments which support their biodiversity and climate objectives. | |

Cost-based approaches | Replacement costs | Benefits: Reflects business costs that would be needed to maintain operations with changes in biodiversity. Can be used to look at the biodiversity underpinning flows of benefits. Limitations: Despite valuing biodiversity requiring measurement of the demand for biodiversity, cost-based methods report the costs that would be associated with a particular action with no relationship to demand. Biodiversity values: Direct, underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Both Examples of use: Businesses can use these approaches to look at the costs of adhering to the mitigation hierarchy (avoid, minimize, restore, offset) as part of a financial analysis of how to mitigate their impacts on biodiversity. The costs of restoration and offsets are examples of replacement costs, and the difference between these costs and costs associated with avoidance and minimization of impacts can represent damage costs avoided. Replacement cost has also been used to highlight the costs of pollinator decline where the next best alternative is hand pollination by humans. The costs of bringing in managed pollinator populations can also be used if this is a feasible alternative. |

Damage costs avoided | ||

Revealed preference (indirect) | Hedonic pricing | Benefits: Can isolate the contribution of particular ecosystem services from biodiversity to human well-being. Limitations: A proxy-based method that may have context-dependent inaccuracies, for example hedonic pricing methods will struggle to distinguish a value of biodiversity if levels of biodiversity are not noticeably variable across the assessment area. Similarly, where there are many potential biodiversity sites in a given area travel costs may be low. To an extent both methods reveal what people have to pay to receive a benefit rather than the value they receive. Biodiversity values: Direct, underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Both Examples of use: Research in England has shown substantial values (reflected in house prices) associated with proximity to high-value biodiversity habitats and designations. This technique allows businesses to understand the values of biodiversity to consumers, and use it to their advantage when considering pricing. For example, a housing developer may be able to determine the benefit of leaving a natural space within their housing development based on the increase in cost of the houses that are in close proximity to the natural area. |

Travel costs | ||

Stated preference | Contingent Valuation (CV) | Benefits: Focus on estimating demand, therefore offer a theoretically justified method to estimate use and non-use values for biodiversity. Non-use values cannot otherwise be easily estimated. Limitations: Highly subjective, and there is often variation between what people claim they are willing to pay with regard to biodiversity (especially summed across a number of surveys) and what is revealed by their behavior and affordable within their budget constraints. Results can be subject to numerous problems connected to participants’ lack of experience attributing monetary values to non-market goods (such as many of the benefits that biodiversity provides to society), and capacity to distinguish values across different levels of their provision (sensitivity to scope). Biodiversity values: Direct, some underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Both Examples of use: Stated preference methods have been applied in different contexts ranging from valuing individual species to estimating the benefits of country-level biodiversity action plans. Businesses can use this approach to understand the wider benefits they are delivering through biodiversity-positive action, and estimate values associated with the impact of biodiversity loss on society. |

Choice Experiments (CE) | ||

Value (benefits) transfer | Benefits: Bypasses requirements for investment in new primary research. Limitations: Relationships between biodiversity and provision of benefits are often complex and context-specific. Value transfer requires the study used as input to have a very similar ecological and socioeconomic context as the current assessment in order to transfer values in a justifiable way. Validity of results is likely to be questionable, especially if the cultural/temporal/ecological context of the source study is not similar. Biodiversity values: Direct, underpinning, insurance, and options Impacts or dependencies: Both Examples of use: Context-specific values for different ecosystem services provided and/or supported by biodiversity (estimated using techniques outlined previously in this table) have been compiled in databases such as the TEEB valuation database (see table MV.2) and can be applied to estimate biodiversity values in similar contexts, or used in different contexts with suitable adjustments. This is the most common technique used by businesses to develop natural capital accounting. For a more detailed example, refer to the case study for Repsol’s natural capital valuation methodology. | |

*The “biodiversity considerations” column in table 7.1 draws heavily from eftec (2015b) and TEEB (2010). Annex B of the Protocol also provides more information about different monetary valuation techniques.

Selection of a valuation technique will often be aligned with the risks and opportunities you identified through your materiality assessment. For example, if your business is facing legal risks from its biodiversity impacts, the consequences could be understood through costs of non-compliance. Alternatively, to understand the business value of your dependency on biodiversity, you could estimate the costs of replacing biodiversity benefits.

See below how a leading energy company is integrating biodiversity within its natural capital valuation methodology.

Company example: Energy companyRepsol, an energy company operating globally, is committed to being at the forefront of the industry in its efforts to measure, mitigate, and minimize the negative impacts of its projects and operations on society and the environment. Repsol is adopting a natural capital approach for environmental decision-making because it enables them to clearly link ecological systems with their contributions to human well-being.

Repsol has developed a novel methodology for the comprehensive valuation of the environmental impacts and dependencies of its projects and operations worldwide, called the Global Environmental Management Index (GEMI). The GEMI has been piloted with Repsol’s operations in the Block 57 concession located in the Amazonia region of Cusco, Peru. This is one of the richest areas for biodiversity in Peru.

The GEMI methodology analyzes improvements (impact reductions) derived from application of the mitigation hierarchy. Environmental impacts are first measured in biophysical units, then converted into monetary values, primarily using value transfer. Modulation factors are then applied to the monetary values to calculate dimensionless “Impact Units.” Repsol has applied the GEMI at Block 57 to estimate the value associated with natural capital loss, comparing the on-ground scenario, where measures to mitigate impacts on biodiversity were implemented, and a counterfactual scenario with no biodiversity mitigation measures. Monetary values for ecosystem services were estimated through collation of 119 values for similar ecosystem services from 27 studies, and then applying site-specific adjustments. Biodiversity is incorporated through adjustment of ecosystem service values for specific biodiversity features, such as the abundance of protected species, and threats such as habitat loss and fragmentation.

Repsol are currently refining the GEMI methodology, and will use the Valuing Guidance to support this process. For example, Repsol can more explicitly consider the importance of biodiversity for delivery of different ecosystem services, and how the economic values for ecosystem services may change with changes in the condition of biodiversity. Furthermore, they can use the Guidance to broaden the scope of their method to also assess business dependencies on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and ensure that limitations to valuation techniques and implications for interpretation of biodiversity valuation results are consistently recognized. Repsol are currently working to ensure these considerations are integrated within their GEMI methodology.

Repsol, an energy company operating globally, is committed to being at the forefront of the industry in its efforts to measure, mitigate, and minimize the negative impacts of its projects and operations on society and the environment. Repsol is adopting a natural capital approach for environmental decision-making because it enables them to clearly link ecological systems with their contributions to human well-being.

Repsol has developed a novel methodology for the comprehensive valuation of the environmental impacts and dependencies of its projects and operations worldwide, called the Global Environmental Management Index (GEMI). The GEMI has been piloted with Repsol’s operations in the Block 57 concession located in the Amazonia region of Cusco, Peru. This is one of the richest areas for biodiversity in Peru.

The GEMI methodology analyzes improvements (impact reductions) derived from application of the mitigation hierarchy. Environmental impacts are first measured in biophysical units, then converted into monetary values, primarily using value transfer. Modulation factors are then applied to the monetary values to calculate dimensionless “Impact Units.” Repsol has applied the GEMI at Block 57 to estimate the value associated with natural capital loss, comparing the on-ground scenario, where measures to mitigate impacts on biodiversity were implemented, and a counterfactual scenario with no biodiversity mitigation measures. Monetary values for ecosystem services were estimated through collation of 119 values for similar ecosystem services from 27 studies, and then applying site-specific adjustments. Biodiversity is incorporated through adjustment of ecosystem service values for specific biodiversity features, such as the abundance of protected species, and threats such as habitat loss and fragmentation.

Repsol are currently refining the GEMI methodology, and will use the Valuing Guidance to support this process. For example, Repsol can more explicitly consider the importance of biodiversity for delivery of different ecosystem services, and how the economic values for ecosystem services may change with changes in the condition of biodiversity. Furthermore, they can use the Guidance to broaden the scope of their method to also assess business dependencies on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and ensure that limitations to valuation techniques and implications for interpretation of biodiversity valuation results are consistently recognized. Repsol are currently working to ensure these considerations are integrated within their GEMI methodology.