This article was written by Andrew Neill, PhD candidate at Trinity College Dublin.

The bioeconomy concept has become widely influential, promising to alleviate environmental degradation while securing economic growth and prosperity for people, capturing the interests of policymakers, researchers, and business leaders alike. But what does “bioeconomy” really mean and how does it relate to a capitals approach?

What is the bioeconomy?

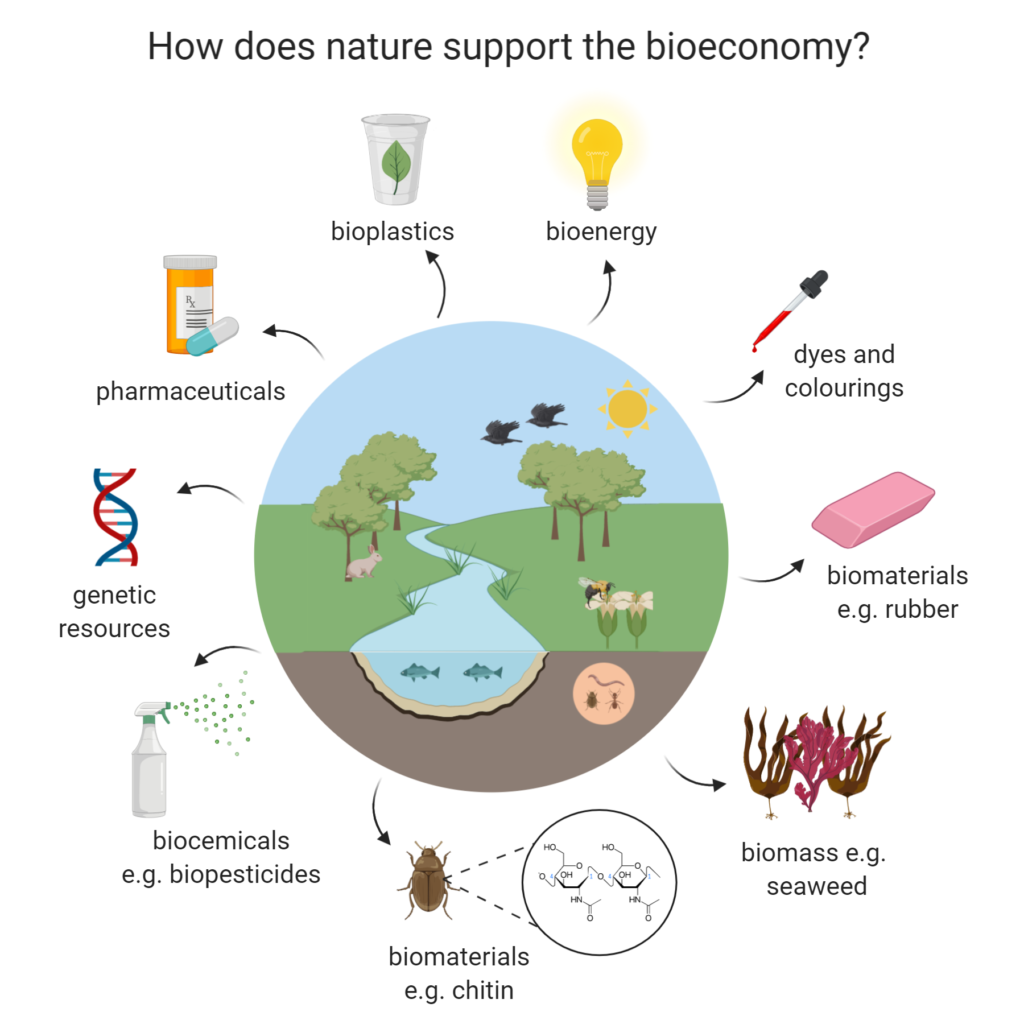

Although lacking a singular definition, the bioeconomy commonly refers to the phasing out of non-renewable, polluting resources and replacing them with biological, renewable alternatives. Simply, the “bio” – “economy” is an economy based on biologically-sourced goods and services, also known as bioresources.

At first glance this may seem unremarkable. Human civilisation has always depended on bioresources: food, medicines, fuels, construction materials, chemicals, dyes, and fibres have all traditionally been rooted in bioresources. In this sense, there is nothing new about basing economies around nature.

What is new are the scientific advances that have broadened the horizons of how we can use bioresources and harness biological processes. Examples of the extraordinary capabilities of the latest biotechnological advancements include microbes that produce drugs and medicines, improved crop varieties that are more productive and resilient, and bio-based fuels produced from organic wastes. We can only imagine what future breakthroughs will become possible. The untapped potential of nature could hold the answers to many of our societal problems, inspiring new technologies, materials and pharmaceuticals.

How does the bioeconomy depend on nature?

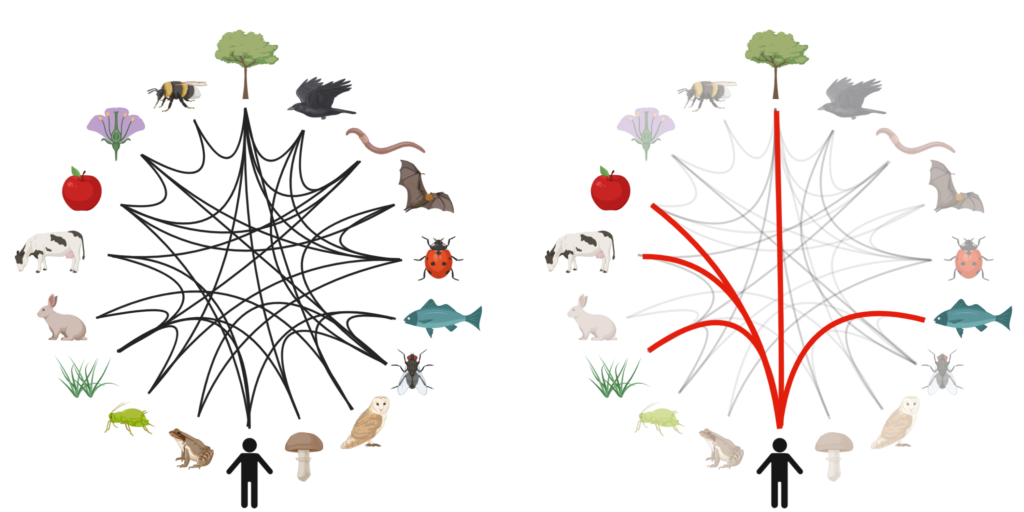

Nature encompasses the wealth of all natural capital stocks. From these stocks, ecosystem services are provided, and some of these ecosystem services give rise to the bioresources that the bioeconomy depends upon. While bioresources are often economically visible, many ecosystem services provide immeasurable benefits that aren’t currently economically recognized—including carbon and nitrogen cycling, mental health benefits and cultural connection. Nature cannot be simplified to solely the provider of bioresources or else we risk losing these essential ecosystem services and their contributions to people’s wellbeing.

Environmental degradation erodes these ecosystem services and narrows the horizon of discovery for future bioeconomy innovators, researchers, and designers. A diverse, healthy and sustainable environment is fundamental to realize the potential of the bioeconomy. If we want to safeguard nature, and in doing so conserve the full suite of nature’s contributions to people, we must consider all of the benefits provided from nature—the unrealized and the unrecognized. In our recently published paper, we argue that current conceptualizations of the bioeconomy can be enhanced through a capitals approach.

Applying a capitals approach to the EU Bioeconomy Strategy

A capitals approach moves beyond understanding our impacts on the world to highlight dependencies on it, too. It contextualizes relationships between the economy, people and planet to redefine value. Crucially, it uses integrated thinking to understand the system change needed to deliver the greatest benefit across the capitals, including natural, social, human and produced capital.

In our paper, we examined the EU Bioeconomy Strategy from a natural capital perspective. First drafted in 2012 and revised in 2018, the strategy envisioned a sustainable EU bioeconomy that capitalised on technological advantages while also creating jobs and growth for its citizens.

Notably, the term “natural capital” was entirely absent from the original strategy, and while “ecosystem services” was included—hinting at some familiarity with the term—it was used broadly and without precision, associated with terms such as “public goods” and “co-benefits”. These “benefits” were viewed as falling outside of the domain of the bioeconomy and thus a secondary priority (with one notable exception relating to carbon sequestration).

The 2012 strategy was centred around increasing the flow of provisioning services (although they were not labelled as such). This is revealed in how the strategy viewed marine ecosystems as “unexplored” with significant growth prophesised from “the unexploited potential of the sea”. The narrow focus on ecosystems as providers of bioresources provided a backdrop to the future potential of the bioeconomy (while fitting neatly into the mainstream economic system), but it failed to recognize the economically invisible value of nature.

Promisingly, the 2018 update to the strategy claimed to place “sustainability in the driving seat” and explicitly acknowledged the “ecological limitations” of the bioeconomy in its opening section. From a natural capital perspective, we identified three key changes:

- The definition of bioeconomy has been updated to include “all sectors and systems that rely on biological resources, their functions and principles. It includes and interlinks land and marine ecosystems and the services they provide”;

- There is recognition of environmental limitations and trade-offs for the bioeconomy; and

- There is new emphasis on the need for data to better understand, monitor and measure ecological limitations.

While the 2018 strategy better aligns with the natural capital concept than its precursor, gaps remain that we believe can be redressed through a capitals approach.

Bridging the gap

Firstly, the language of natural capital and ecosystem services should be better integrated into bioeconomy policy. Strikingly, “natural capital” remains missing entirely, while “ecosystem services” and “functions” are mentioned but without precision or refinement. By fully embracing the specificity and terminology of the natural capital framework—such as natural capital attributes and ecosystem service classifications—ambiguous meanings could be resolved while also aligning with other EU policy that has embraced this language, including the EU Green Deal and the Biodiversity Strategy 2030.

Secondly, decision-making within the bioeconomy should target natural capital stocks, not the flow of services. Objectives and trade-offs are too often viewed in terms of service flows to people, but we can’t manipulate those services directly. Instead, we can manipulate natural capital stocks in terms of their quantity, quality, or spatial arrangement in ways that will lead to the downstream desired change in service flow.

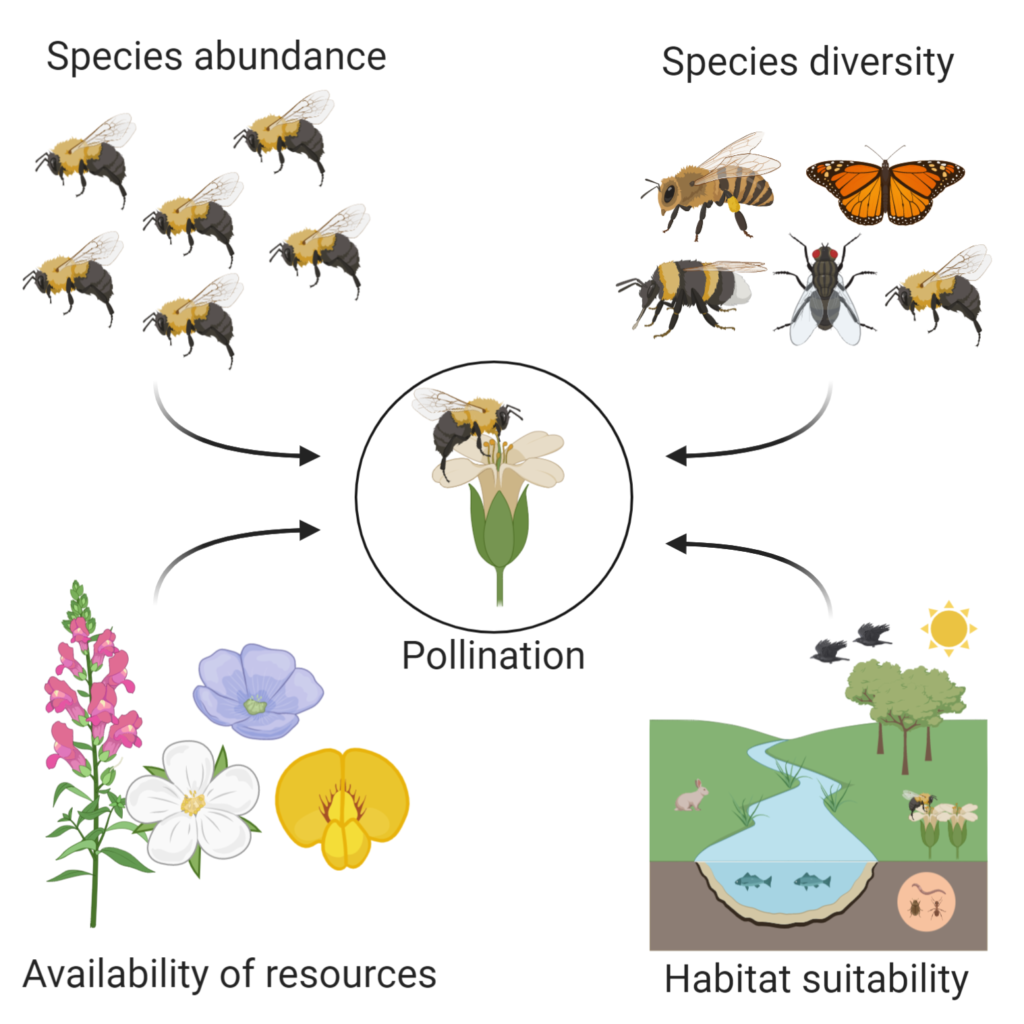

The bioeconomy should account for the complexity of how natural capital stocks, their functions and their interactions give rise to service flows. For example, the 2018 strategy highlights the role of biodiversity for providing valuable pollination services. However, pollination depends on numerous natural capital stocks, not just biodiversity. Joined-up, integrated thinking that embraces this complexity is needed to make optimal management decisions.

Finally, the bioeconomy can benefit from knowledge produced from other natural capital related projects to better understand its “ecological limitations”. For example, natural capital accounting takes stock of our ecosystems and the services they provide. The data and analyses generated from such projects are highly relevant to the bioeconomy, but those connections have not yet been drawn. There is undoubtedly a constellation of relevant natural capital research going on across disciplines, but advances are limited by the lack of information flow. A report from the Capitals Coalition, Data Information Flow, outlines critical ways to bridge this gap, and can help align natural capital expertise and bioeconomy practitioners to guide the bioeconomy towards its environmental obligations.

The future of the bioeconomy

We don’t know exactly how the bioeconomy will change society’s relationship with nature in the future, but a capitals approach can provide a shared language to facilitate collaboration across disciplines, serve to unify policy targets towards a shared objective to safeguard the environment, and create the tools to capture our evolving values and priorities as we continue to develop a sustainable bioeconomy.

This article is based on Andrew Neill’s recently published paper and his PhD research exploring bio-economic activities in Ireland and their implications for Ireland’s natural capital. Find out more about Natural Capital Ireland here and connect with Andrew here.